Binocular Universe: For the Birds

Discuss this article in our forums

|

|

Binocular Universe:For the BirdsAugust 2014

|

This month’s column is for the birds. Literally, as we visit a nebulous aviary along the gentle stream of the southern Milky Way populated by a swan and an eagle. We paid a call here last summer, when we focused on M24, the Small Sagittarius Star Cloud. This year, we return to explore a few more showstoppers in and around the area.

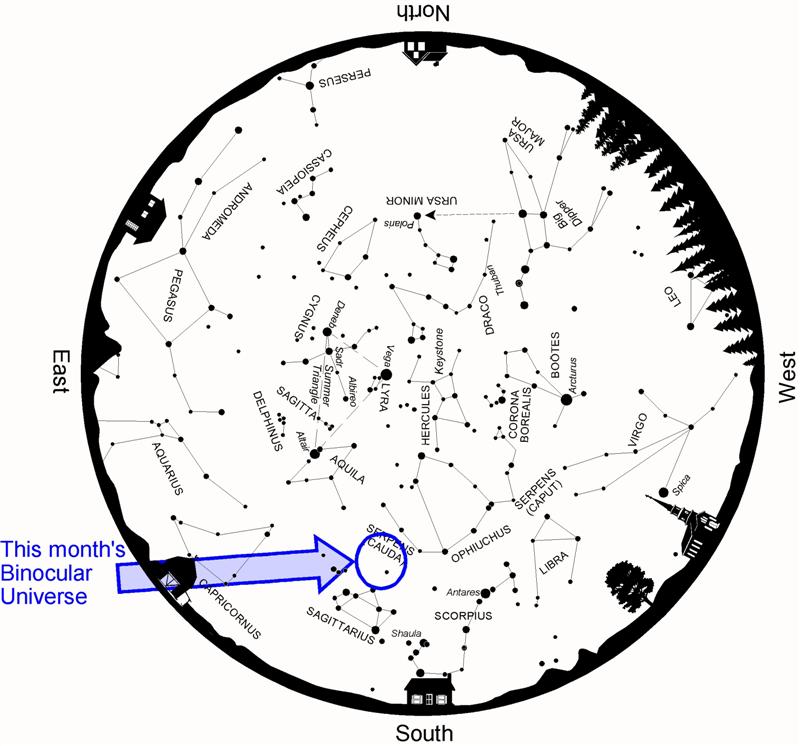

Above: Summer star map from Star Watch by Phil Harrington.

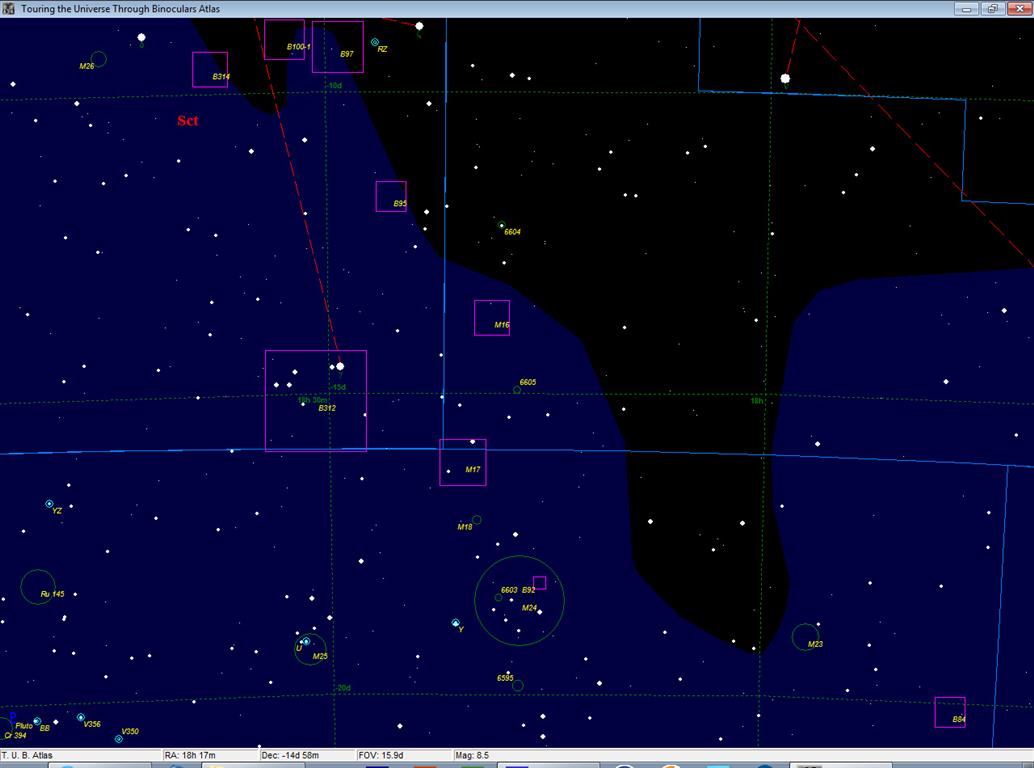

Above: Finder chart for this month's Binocular Universe.

Chart adapted from Touring the Universe through Binoculars Atlas (TUBA)

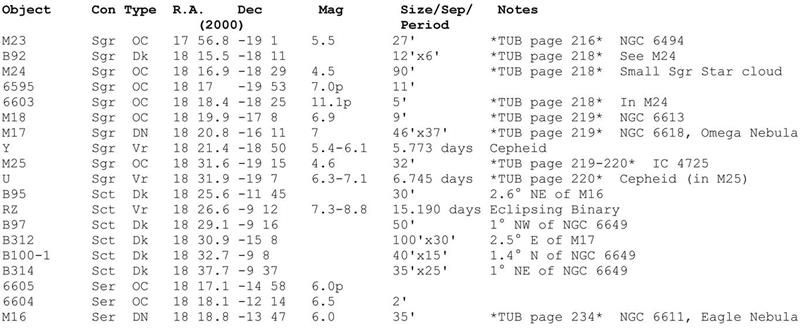

North of M24, along the hazy lane of our galaxy, lay three more members of Charles Messier’s catalog: M16, M17, and M18. All three fit into the field of my 10x50 binoculars, making them fun to compare. Let's take a look at each. We will begin with the southernmost of the trio, M18, and work our way northward.

Messier himself was first to

bump into his catalog’s 18th member. He spotted it on

Of the three Messier targets profiled this month, I have to admit that M18 is the least impressive. But thanks in large part to its surroundings and the company it keeps, it still presents a pleasant view through binoculars.

Some 40 stars populate this open cluster, all residing a little more than 4,200 light years away. The brightest of the bunch are set in a triangular pattern that may just be glimpsed in 10x50s, but only under dark conditions. The rest blend into a small knot of hazy starlight.

Studies of the stars’ spectra given an overall age of the cluster as about 50 million years. That’s relatively young as star clusters ago. But, as we will see in a moment, M18 is considerably older than our next two targets.

M17 is one of my favorite summertime targets and is an easy catch through nearly all binoculars. The Swiss observer Phillippe Loys de Chéseaux was first to lay eyes on it in 1746 (N.B. some references say 1745), when he described: “It has perfectly the form of a ray, or of the tail of a comet, of 7' length and 2' width; its sides are exactly parallel and rather well terminated, as are its two ends. Its middle is whiter than the borders.”

Interestingly, Messier did not know of de Chéseaux’s discovery when he first spied it that same evening of June 3rd in 1764. So, even though he was technically beaten to the punch, we still must give Messier kudos for a great find. He saw it as: “A train of light without stars, of 5 or 6 minutes in extent, in the shape of a spindle, and a little like that in Andromeda's belt [M31].”

M17 is located just to the south of a yellowish 5th-magnitude star and less than half a binocular field north of M18. If you're viewing through 50-mm and smaller binoculars, look for a straight "bar" of grayish light oriented more or less southeast-northwest. Larger binoculars add a faint hook-shaped appendage curving off the western end of the bar.

It's this hook-and-bar shape that has given rise to one of M17's nicknames, the Swan Nebula. Through telescopes, the bar represents the swan's floating body, while the hook turns into its long, graceful neck and head. My 16x70 binoculars portray the swan as floating upside down, which I find worrisome. Telescopes, of course, invert the view to show that the swan is alive and well.

Like the Orion Nebula, M42, M17 is an active star-forming region. A young star cluster lies hidden amid and behind the clouds of M17, though we are hard-pressed to see them directly. None of the more than 8,000 to 10,000 cluster members are more than a million years old, mere babes in the heavens. They are separated from us by 5,900 light years.

M17 is better known by a second nickname, the Omega Nebula. That analogy stems from an observation made by John Herschel in 1823, when he wrote “A large extended nebula; its form is that of a Greek Omega…” You would likely need the aperture of a telescope, however, to see the full horseshoe shape that led to Herschel’s comment.

Finally, we cross into Serpens to find the open cluster M16. Like M17, M16 was first eyed by de Chéseaux in 1746 (or maybe 1745, depending on who you ask) and independently found by Messier on the busy night of June 3, 1764. Messier described a “Cluster of small stars, mingled with a faint glow.” True, the stars of M16 are mingled with the faint glow of ionized hydrogen – the so-called Eagle Nebula – but Messier did not see that. Instead, his description points to stars too faint for his telescope to resolve. The nebula that today we call the Eagle Nebula was not discovered until 1895 by Edward Barnard. It was subsequently cataloged separately as IC 4703.

The view through binoculars matches Messier’s words very closely. With my 10x50s, I can count about a dozen stars against the unresolved glow of fainter suns. With my 25x100 giants and nebulae filters held between eyepieces and eyes, I can catch hints of the nebula itself, but only on the best nights.

Studies show that M16 is one of the youngest star clusters known, perhaps no more than five million years old, affording astronomers an excellent laboratory for study. Its hottest stars, spectral type O, are seven times hotter than our Sun. M16 is estimated to be 5,600 light years away.

M16 (actually, IC 4703) captured the public’s imagination when the Hubble Space Telescope’s “Pillars of Creation” photograph was released in 1995. This has to be one of the most dramatic views of the Universe captured in recent years. There, created by a process known as photo-evaporation, columns composed of cooled hydrogen and dust appear to be reaching into the surrounding cloud, as if to grasp at the stars spawned within. The Space Telescope Science Institute notes that as the pillars themselves are slowly eroded away, small globules of even denser gas buried within the pillars are uncovered, dubbed "EGGs," an acronym for Evaporating Gaseous Globules. Eventually, most these embryonic suns will evolve into mature stars.

As you can see from the chart above, there are plenty of other targets in the immediate area. If you have the chance to view under dark, transparent skies, try your luck with a couple of the dark nebulae toward the eastern half of the chart. Here are some details.

Questions, comments, suggestions? Let’s talk! Post them in this blog’s discussion forum. Until next month, remember that two eyes are better than one.

|

|

About the Author: Phil Harrington is a contributing editor to Astronomy magazine and author of 9 books on astronomy. Visit his web site at www.philharrington.net |

|

Phil Harrington's Binocular Universe is copyright 2014 by Philip S. Harrington. All rights reserved. No reproduction, in whole or in part, beyond single copies for use by an individual, is permitted without written permission of the copyright holder. |

|

- Charlie Hein, droid, John O'Hara and 2 others like this

0 Comments